Magic in Anglo-Saxon England

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Magic in Anglo-Saxon England refers to the belief and practice of magic by the Anglo-Saxons between the fifth and eleventh centuries AD in Early Mediaeval England. In this period, magical practices were used for a variety of reasons, but from the available evidence it appears that they were predominantly used for healing ailments and creating amulets, although it is apparent that at times they were also used to curse.

The Anglo-Saxon period was dominated by two separate religious traditions, the polytheistic Anglo-Saxon paganism and then the monotheistic Anglo-Saxon Christianity, both of which left their influences on the magical practices of the time.

What we know of Anglo-Saxon magic comes primarily from the surviving medical manuscripts, such as Bald's Leechbook and the Lacnunga, all of which date from the Christian era.

Written evidence shows that magical practices were performed by those involved in the medical profession. From burial evidence, various archaeologists have also argued for the existence of professional female magical practitioners that they have referred to as cunning women. Anglo-Saxons believed in witches, individuals who would perform malevolent magic to harm others.

In the late 6th century, Christian missionaries began converting Anglo-Saxon England, a process that took several centuries. From the 7th century on, Christian writers condemned the practice of malevolent magic or charms that called on pagan gods as witchcraft in their penitentials, and laws were enacted in various Christian kingdoms illegalising witchcraft.

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

Following the withdrawal of the Roman armies and administrative government from southern Britain in the early 5th century CE, large swathes of southern and eastern England entered what is now referred to as the Anglo-Saxon period. During this, the populace appeared to adopt the language, customs and religious beliefs of the various tribes, such as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, living in the area that covers modern Denmark and northern Germany. Many archaeologists and historians have believed that this was due to a widespread migration or invasion of such continental European tribes into Britain, although it has also been suggested that it may have been due to cultural appropriation on behalf of native Britons, who wished to imitate such tribes.[1]

Either way, the Anglo-Saxon populace of England adopted many cultural traits that differed from those in the preceding Iron Age and Romano-British periods. They adopted Old English, a Germanic language that differed markedly from the Celtic and Latin languages previously spoken, whilst they apparently abandoned Christianity, a monotheistic religion devoted to the worship of one God, and instead began following Anglo-Saxon paganism, a polytheistic faith revolving around the veneration of several deities. Differences to people's daily material culture also became apparent, as those living in England ceased living in roundhouses and instead began constructing rectangular timber homes that were like those found in Denmark and northern Germany. Art forms also changed as jewellery began exhibiting the increasing influence of Migration Period Art from continental Europe.

Paganism and Christianity[edit]

Anglo-Saxonist scholar Bill Griffiths remarked that it was necessary to understand the development of the pantheon of Anglo-Saxon gods in order to understand "the sort of powers that may lie behind magic ritual."[2] He argued that the Anglo-Saxon pagan religion was "a mass of unorganised popular belief" with various traditions being passed down orally.[3]

Terminology[edit]

The language of the Anglo-Saxons was Old English, a Germanic language descended from those of several tribes in continental Europe. Old English had several words that refer to powerful women associated with divination, magical protection, healing and cursing.[4] One of these was hægtesse or hægtis, whilst another was burgrune.[4]

Another Old English term for magicians was dry, making them practitioners of drycraeft. Etymologists have speculated that the latter word might have been an anglicised term for the Irish drai, a term referring to druids, who appeared as anti-Christian sorcerers in much Irish literature of the period.[5] In this case, it would have been a term borrowed from the Celtic languages, which were widespread across southern Britain prior to the Anglo-Saxon migration.[6]

Sources[edit]

From the Early Mediaeval to the present day, much information about the Anglo-Saxons and their magical practices have been lost. What we do know comes from a small selection of historical and archaeological sources that have been able to survive.

Medical manuscripts[edit]

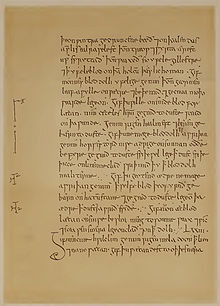

The "main sources of our knowledge of magic" in the Anglo-Saxon period are the surviving medical manuscripts from the period.[7] The majority of these manuscripts come from the 11th century, some being written in Old English and others in Latin, and they are a mix of new compositions and copies of older works.[8] Three main manuscripts survive, now known as Bald's Leechbook, the Lacnunga and the Old English Herbarium, as do several more minor examples.[8]

Remarking on the magico-medical knowledge of the Anglo-Saxons, historian Stephen Pollington noted that the amount "actually recorded was probably only a fraction of the total available to the communities of old, since not everybody had the time and skill to write down what they knew; and furthermore that the few records that survive are only a small part of the corpus: in the thousand years since our surviving manuscripts were written there have been a multitude of cases of accidental or deliberate destruction."[9]

Bald's Leechbook was written around the middle of the 10th century, and is divided into three separate books.[7] Written at the Winchester scriptorium that had been founded by the King of Wessex Alfred the Great (848/849–899), it is a copy of an earlier work that may have been written during Alfred's reign.[10] The first two books in the Leechbook are a collation of Mediterranean and English medical lore, whilst the third is the only surviving example of an early English medical textbook.[10] This third book contains remedies listed under which part of the body they are supposed to heal, with plants described under their Old English (rather than Latin) names. This implies it was written before the later Mediterranean influence that came with Christianisation.[10] In contrast with the first two parts of the Leechbook, the third contains more magical instructions, with longer and more complicated charms and a greater folkloric component.[10]

The second of these sources is the Lacnunga, a medical manuscript that opens with an Old English translation of the Herbarium Apulei, a description of plants and herbs found throughout classical and mediaeval Europe.[11] The individual who had originally compiled the Lacnunga started with recipes to heal such ailments as headaches, eye pains and coughs, but whenever "he came across anything that struck his fancy for some reason or other, he immediately put it in without bothering about its form or the order of his book", leaving the work disjointed.[12] The name "Lacnunga" does not itself appear in the manuscript, but was given to the work by the Reverend Oswald Cockayne who first edited and published it into modern English in the third volume of his Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft of Early England (1866).[13]

Storms compared the Leechbook and the Lacnunga, arguing that if the former had been "the handbook of the Anglo-Saxon medical man", then the latter was more like "the handbook of the Anglo-Saxon medicine-man", placing a greater emphasis on magical charms and deviating from normal medical manuscripts in style.[14] "

Source and more

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_in_Anglo-Saxon_England